WHY NEED FOR WORKER’S SAFETY WAS FELT? A BRIEF HISTORICAL VIEW TO CLEAR OUT THE CIRCUMSTANCE

In 1969, a study of industrial accidents was undertaken by Frank E. Bird, Jr., who was then the Director of Engineering Services for the Insurance Company of North America. He was interested in the accident ratio of 1 major injury to 29 minor injuries to 300 no-injury accidents first discussed in the 1931 book, Industrial Accident Prevention by. H. W. Heinrich. Since Mr. Heinrich estimated this relationship and stated further that the ratio related to the occurrence of a unit group of 330 accidents of the same kind and involving the same person, Mr. Bird wanted to determine what the actual reporting relationship of accidents was by the entire average population of workers. H.W. Heinrich’s classic safety pyramid is now considered the foremost illustration of types of employee injuries. There Bird analyzed 1,753,498 accidents reported by 297 cooperating companies. These companies represented 21 different industrial groups, employing 1,750,000 employees who worked over 3 billion hours during the exposure period analyzed. The study revealed the following ratios in the accidents reported: For every reported major injury (resulting in fatality, disability, lost time or medical treatment), there were 9.8 reported minor injuries (requiring only first aid). For the 95 companies that further analyzed major injuries in their reporting, the ratio was one lost time injury per 15 medical treatment injuries. Forty-seven percent of the companies indicated that they investigated all property damage accidents and eighty-four percent stated that they investigated major property damage accidents. The final analysis indicated that 30.2 property damage accidents were reported for each major injury. Part of the study involved 4,000 hours of confidential interviews by trained supervisors on the occurrence of incidents that under slightly different circumstances could have resulted in injury or property damage. Analysis of these interviews indicated a ratio of approximately 600 incidents for every reported major injury. In referring to the 1-10-30-600 ratio detailed in a pyramid it should be remembered that this represents accidents reported and incidents discussed with the interviewers and not the total number of accidents or incidents that actually occurred. Bird continues, as we consider the ratio, we observe that 30 property damage accidents were reported for each serious or disabling injury. Property damage incidents cost billions of dollars annually and yet they are frequently misnamed and referred to as “near-accidents”. Ironically, this line of thinking recognizes the fact that each property damage situation could probably have resulted in personal injury. This term is a holdover from earlier training and misconceptions that led supervisors to relate the term “accident” only to injury.

The 1-10-30-600 relationships in the ratio indicate clearly how foolish it is to direct our major effort only at the relatively few events resulting in serious or disabling injury when there are so many significant opportunities that provide a much larger basis for more effective control of total accident losses. It is worth emphasizing at this point that the ratio study was of a certain large group of organizations at a given point in time. It does not necessarily follow that the ratio will be identical for any particular occupational group or organization. That is not its intent. The significant point is that major injuries are rare events and that many opportunities are afforded by the more frequent, less serious events to take actions to prevent the major losses from occurring. Safety leaders have also emphasized that these actions are most effective when directed at incidents and minor accidents with a high loss potential. There is always a large variation between the most serious and no claim incident, as shown in both pyramids. In 2003, ConocoPhillips Marine conducted a similar study demonstrating a large difference in the ratio of serious accidents and near misses. The study found that for every single fatality there are at least 300,000 at-risk behaviors, defined as activities that are not consistent with safety programs, training and components on machinery. These behaviors may include bypassing safety components on machinery or eliminating a safety step in the production process that slows down the operator. With effective machine safeguarding and training, at-risk behaviors and near misses can be diminished. This also reduces the chance of the fatality occurring, since there is a lower frequency of at-risk behaviors. The variation can be explained by distance or time – for example, the injury was missed by one second or by one inch. Machine safety can make a material. The difference in widening the variation, favorably impacting frequency and severity of claims and, therefore, workers’ compensation premiums.

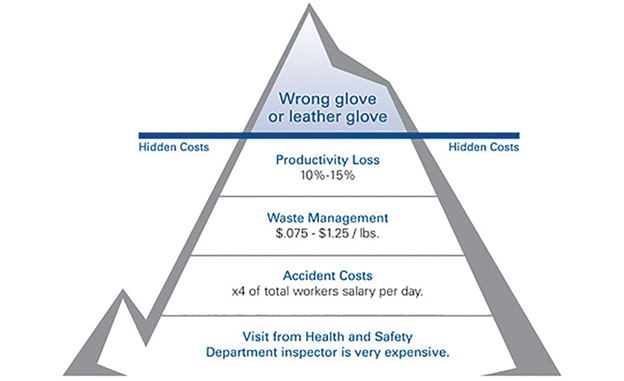

DIRECT AND INDIRECT (INSURED & UNINSURED COSTS OF ACCIDENT)

Direct Costs of accidents and incidents

These costs are readily measurable

- Damage to premises, plant and equipment

- Sick pay

- Overtime to cover injured person

- Fines

Indirect Costs of accidents and incidents

These costs are more difficult to quantify

- Loss of an employee’s skills and work output

- Downtime during investigations and pay of people investigating

- Training costs for replacement operators

- Lost Orders

- Increased Insurance Premiums

- Defending criminal and civil prosections

- Fines

- Compensation Claims

- Workplace effects: poor productivity due to low morale

- Effects on sales: increasingly larger companies will not place orders with suppliers who have a poor health & safety record or cannot demonstrate effective management of risks.

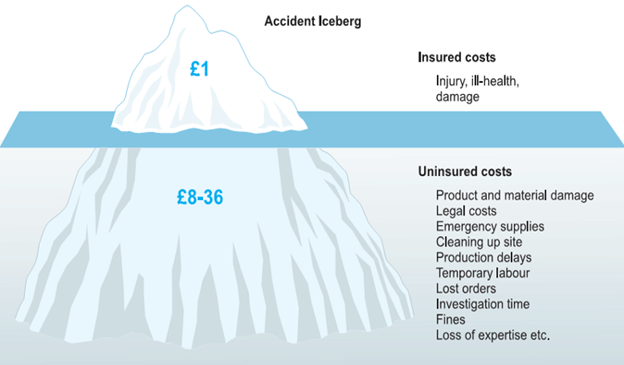

Of course some costs can be covered by insurance (employer’s liability, public liability, vehicles) but many of the costs associated with accidents and incidents cannot be covered, and even those which are will be subject to an excess in many cases. The HSE reported findings of studies (HSG96 Costs of Accidents at Work) which showed the indirect costs of accidents are between 8 and 36 times greater than the direct costs. Good health and safety management not only controls costs but provides increased opportunities for profit through better morale in the workforce (improvements in productivity) and the ability to tender for orders which would not otherwise be considered by large, public facing organizations.